Why Beyoncé And Lizzo Saying "Spaz" Is Complicated

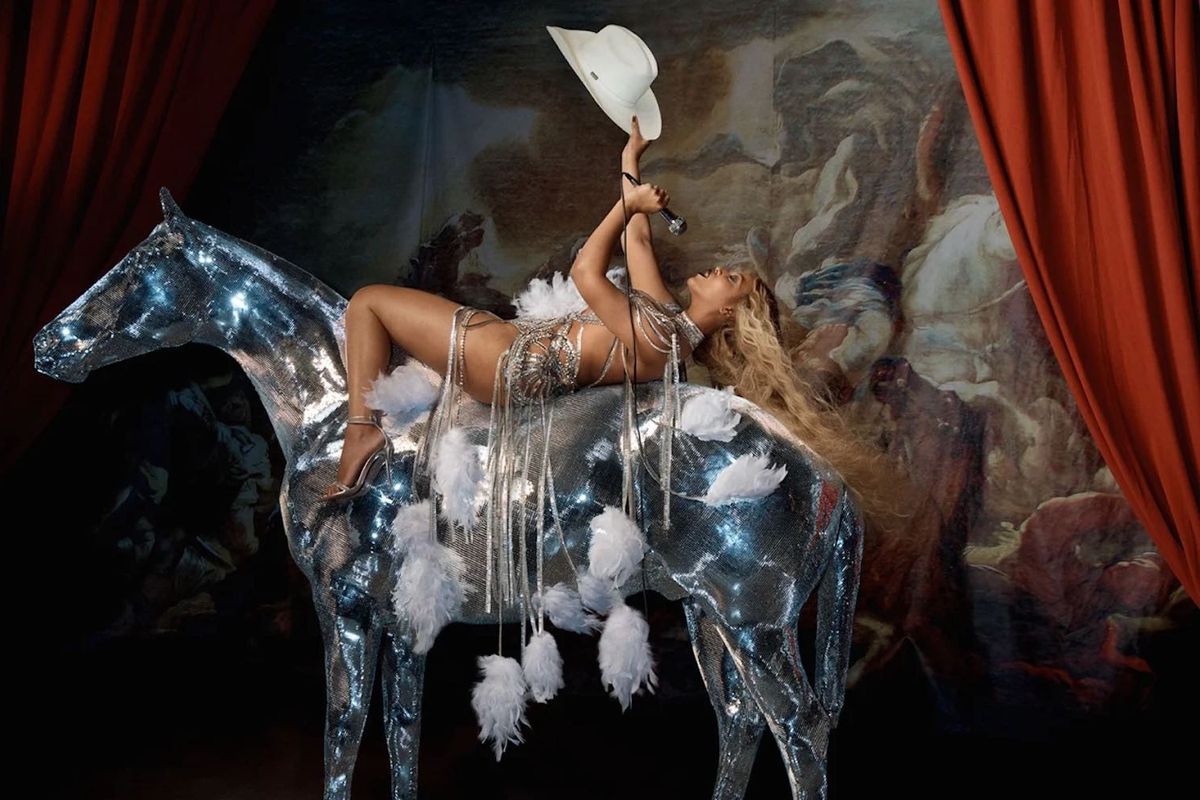

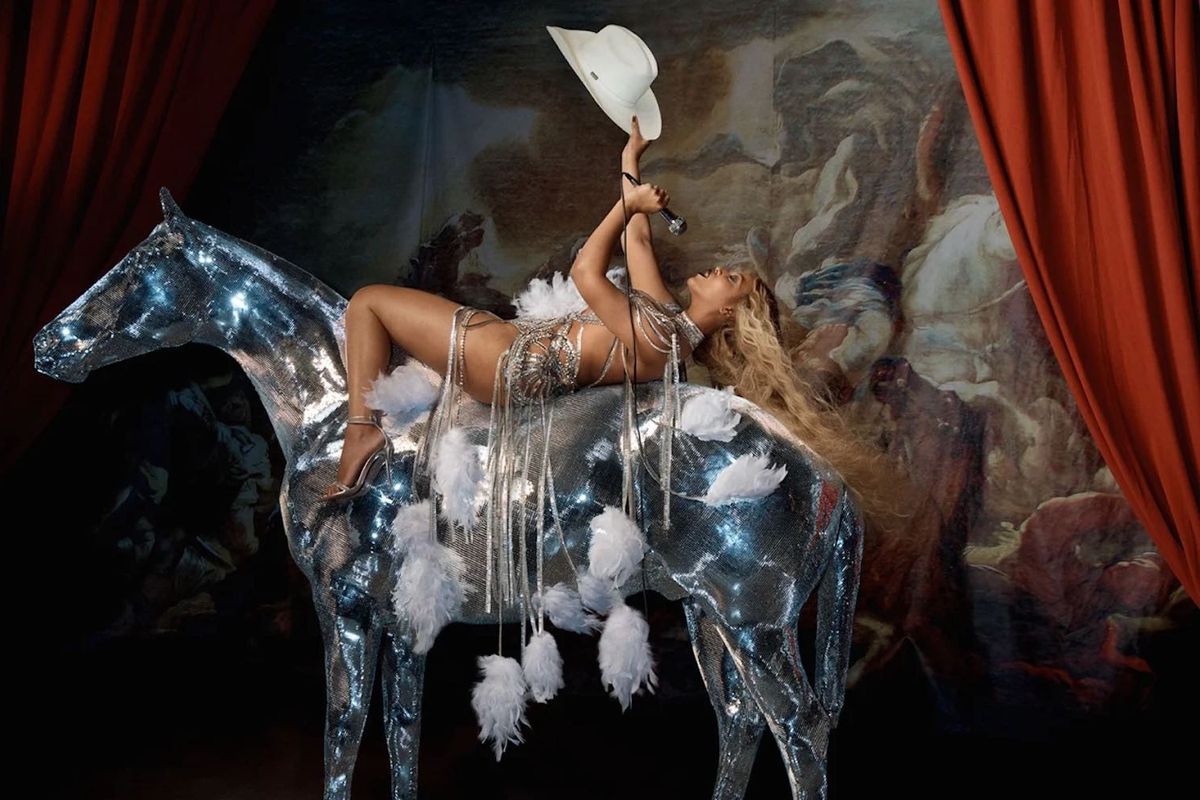

Photo Credit: Mason Poole

To continue reading

Create a free account or sign in to unlock more free articles.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Register

The content is free, but you must be subscribed to Okayplayer to continue reading.

THANK YOU FOR SUBSCRIBING

Join our newsletter family to stay tapped into the latest in Hip Hop culture!

Login

To continue reading login to your account.

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Beyoncé has already reached critical acclaim with her newest solo album, Renaissance. From the project having a 9.5 rating on metacritic to fans describing the album as “iconic” on social media, it’s an album that truly encapsulates the renaissance period perfectly. However, praise for Beyoncé’s genius is not the only conversation being had. The well-beloved artist found herself in hot water after disability advocates on Twitter brought attention to her use of “spaz” in her song “Heated.” This comes only two months after Lizzo received backlash for using the same word in “Grrrls.”

Disabled advocates, mainly from the UK, expressed anger with Lizzo after using the word spaz in her lyrics, because it is known as a derogatory term against individuals with cerebral palsy. Spaz, short for “spastic,” references the inability for a disabled person to control their movements. As an African American, the information felt brand new. Personally, I had grown familiar with Black artists using the terminology in music, especially during the ‘90s era of hip-hop. Spaz was not used to make fun of the disabled community, but as a descriptor for “going wild,” usually for when one is partying and losing themselves to the atmosphere. I also have heard “spaz” in the context of someone on the brink of irritation or annoyance. I saw “spaz” as what it had always been to me — African American Vernacular English (AAVE).

Now, I am not using the history of spaz in AAVE to dismiss the harm that the slur has caused to the disabled community. As a Black disabled person, I wish to open dialogue concerning the policing of AAVE alongside the erasure of Black disabled voices in this discussion. The majority of public call-outs were tweeted by white disability advocates in the UK. While their frustration was justified, it is unrealistic for them to expect an American to know that a term primarily used in the UK was derogatory. When I started a dialogue about spaz in the context of AAVE on my Twitter account, many white disabled British people took it as a sign for reverse racism. To white people, me requesting that they consider Black disabled voices was oppression.

In my experience, white people will use any ounce of marginalization they possess to justify drowning out the voices of those who should be prioritized in the conversation. Many self-proclaimed allies rarely use their huge followings to uplift the communities they claim to be in solidarity with. Are you genuinely upset that someone perpetuated harm? Or do you only feel harmed when your favorite white artist isn’t the culprit? Your outcry needs to be the same across the board.

This especially affects Black women and femmes like Lizzo and Beyoncé, because we’re held to a higher standard. Historically, Black female artists are not allowed to make the same mistakes white artists do. For white artists, it is a “learning” moment that deserves the benefit of the doubt. Black disabled advocate Ola Ojewumi pointed out that there are plenty of white musicians who have used ableist language in past songs and album titles, who haven't experienced a fraction of the vilification that Black women and femmes do. Anti-blackness begins to rear its ugly head, but Lizzo and Beyoncé won’t experience it in the same way.

Lizzo’s identity as a fat Black woman already makes her an easy target for anti-blackness and fatphobia. This fueled the fire even more when she was called out for her usage of spaz. Not even taking full accountability and swiftly re-recording the song saved her from intense ridicule. Lizzo showed an example of what it actually means to be in community with someone. White musicians write an apology without even muttering the words “I’m sorry,” and suddenly all is well again.

Beyoncé faced similar criticism but there are some key differences in how both were handled. No one fought for Lizzo as much as they did for Beyoncé. It’s unsuprising that someone as iconic as Beyoncé is well-shielded when it comes to criticism. She’s untouchable in a way — a figure in the Black community that can do no wrong. Lizzo, on the other hand, often doesn't get that same support from Black people, with many accusing her of making music for white people, a notion that dismisses how vocal she's been about making music that affirms Black women. Beyoncé seems to have walked away unscathed, a luxury that Lizzo wasn’t afforded.

When approaching this discussion, I want to emphasize that I am only one voice in the Black disabled community. While I was unaware that spaz was a slur, it does not erase the fact that it is a slur actively used against Black disabled people. The discussion surrounding AAVE is important, but it should not be used to dismiss the Black disabled community. To quote Black disabled advocate Imani Barbarin, the nondisabled Black community treats the discussion of disability as“white people shit”, which for them, serves as a justification for using the slur.

I want people to know that many things can be true at once: words and their meanings are not universal; Black women and Femmes are held to a higher standard; AAVE is an explanation but not justification for the slur’s usage (and it needs to be dropped from our vocabulary immediately); and white people should be aware of when they are policing language in Black music and everyday Black conversation. Most importantly, Black disabled advocates need to be prioritized in a conversation that includes an aspect of intersectionality and marginalization that white disabled people will never be able to speak on.

__

Clementine Williams is a poet and fiction writer hailing from North Carolina. They are the author of Remedies For A Cavity (Ethel Zine and Micro Press, 2022).