The 9/11 terrorist attacks were a unifying moment for the US. Hip-hop had a more complicated relationship: part patriotic, part provocative. No act better exemplified this than Dipset.

In 2001, two hijacked planes crashed into the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York City, killing nearly 3,000 people and injuring thousands more. New York City Mayor at the time Rudy Giuliani said that “the attacks of September 11th were intended to break our spirit. Instead, we have emerged stronger and more unified.” Former President George W. Bush decreed that “one of the worst days in America’s history saw some of the bravest acts in Americans’ history.” And rapper Cam’ron said “I ain't mad that the Towers fell. I'm mad the coke price went up, and this crack won't sell.” It was a very different response, offering commentary on the drug market that the average political pundit probably never considered.

The terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, were a unifying moment for most of the United States. Hip-hop had a more complicated relationship: one part patriotic, one part provocative. No act better exemplified this than Harlem collective The Diplomats.

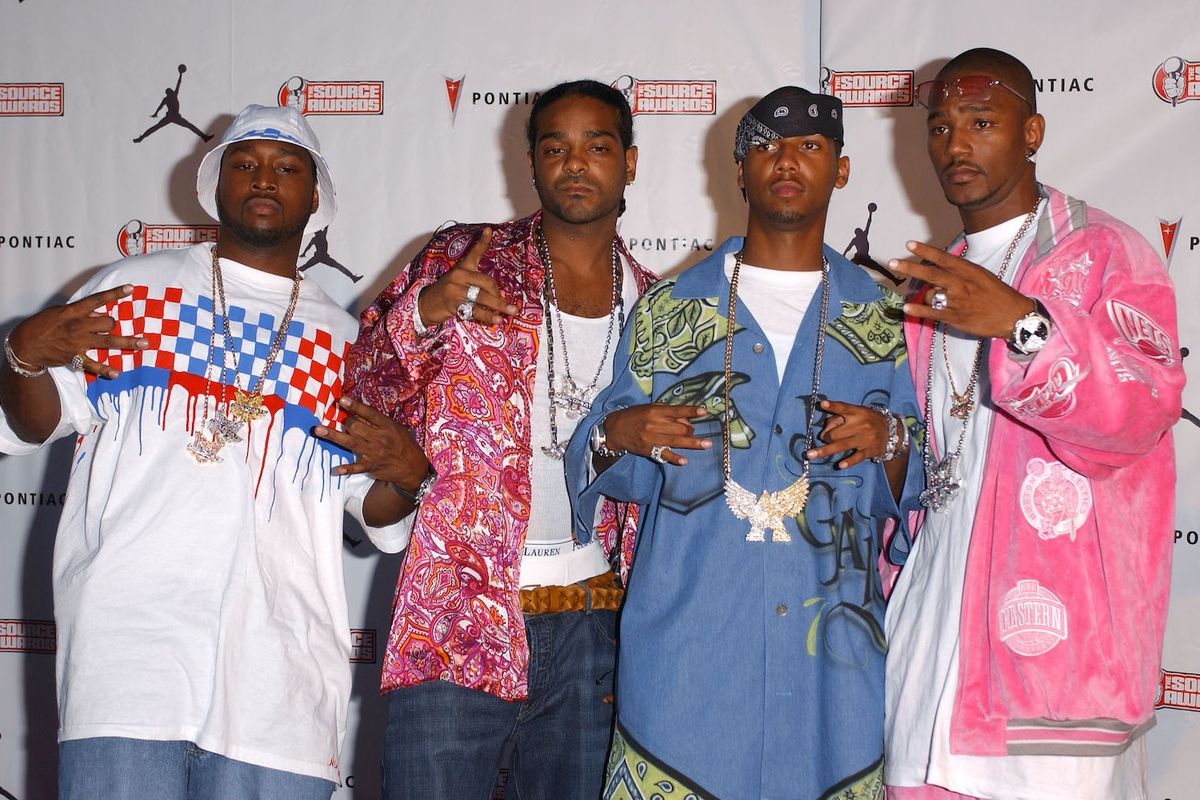

In September 2001, Cam’ronwasn't yet a rap icon. He was just a fledgling rapper looking for a break. Cam’ron's rap beginnings came in the '90s, as a member of underground rap group Children of The Corn, alongside Big L, "Murda" Mase, Herb McGruff, and Cam'ron's late cousin Bloodshed. He later achieved modest success as a solo artist, going gold with his debut Confessions of Fire — which spawned the minor hit "Horse & Carriage." But after a frustrating stint with Sony's Epics Records, he forced himself off the label and signed to his childhood friend Dame Dash’s Roc-A-Fella Records in December 2001 — two months after the 9/11 attacks. He dropped Diplomats, Volume 1 in early 2002, a project that is often given credit for launching the golden era of mixtapes in the 2000s. He would drop Diplomats, Volume 2 later that year. By that point, Cam’ron’s Roc-A-Fella debut, Come Home With Me, had established him as a star. And he had officially debuted his crew: The Diplomats, aka Dipset, with his friend Jim Jones and hungry young MC Juelz Santana. (Juelz Santana dropped memorable verses on Come Home With Me singles “Oh Boy” and “Hey Ma” which pegged him to be next in line for a solo deal.)

Early 2002 was also a fateful period for President Bush, whose post-911 messaging presented a “good guys vs. bad guys” narrative in order to instill support for an eventual “War on Terror.” The administration and American public were the good guys, while Al Qaeda and their potential allies were the bad guys. In the midst of their rise, Dipset marked themselves as rap antiheroes that culled inspiration from both sides of the binary.

The crew played up patriotic imagery with an eagle as their logo and heavy red-white-and-blue fashion. On the group's masterful double album, Diplomatic Immunity, they had a song called "Ground Zero" where they declared that they made “9/11 music." However, they also called themselves “the Dipset Taliban” and “Harlem’s Al Qaeda” and compared themselves favorably to Al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden. ("I'm the realest thing popping since Osama bin Laden, so pay homage...")

On “I Love You,” Juelz Santana was empathetic to 9/11 victims with lines like “broken pieces of towers left as their graves.” But in the original version of the song, he rhymed, “I worship the prophet, the great Mohammed Omar Atta, for his courage behind the wheel of the plane. Reminds me when I was dealin’ the ‘caine.” Atta is believed to have piloted one of the planes into the World Trade Center on 9/11. The line was taken out of the version of the song that appeared on Diplomatic Immunity album, but not before causing controversy.

In 2002, Santana told NME.com the following about the line:

I feel my Diplomats are my team and I’m going to do whatever it takes for them, for my people, the same way as he did for his people. Not that I support him or what he did, but in order for him to do that, it had to take courage and love for what he believed in. A lot of New York people don’t have that. Maybe if they did, something like that wouldn’t happen.

Santana’s response reflected the immaturity of the then-20-year-old and his crew. But it also exemplifies that there are no sacred cows in hip-hop. Rappers love to push the envelope with similes devised to leave fans open-mouthed at both their function and shock value, no matter who gets hurt in the process. Santana added that, “if 9/11 had had never happened, I would have never been able to sing that. It’s because United States has been going over there trespassing, stealing their stuff… now they make it seem like they came over here and bombed us for nothing.”

Perhaps Santana’s comment is why the crew felt justified calling themselves The Taliban. Dipset adorned the cover of theirDiplomats Volume 4 mixtape with a stamp that read “Taliban, Fuck Da Man, I’m Da Man.” In 2004, KRS-One sparked controversy when he surmised that he and other Black people “cheered” 9/11 because the World Trade Center symbolized a racist American establishment. He told attendees of the 2004 The New Yorker Festival that “9/11 happened to them, not us.” His comments were harsh, but reflect a sentiment of detachment from white America that Black people feel to this day. While we’re told to “never forget” 9/11, state-sanctioned violence and assaults against the Black community — like the 1921 Tulsa bombing or the 1985 MOVE bombing — don’t receive similar commemoration. That “them and us” mindset is what paved the way for Dipset to simultaneously be victims but feel detached enough to harbor twisted esteem for the entities who had stuck one to “the man.”

The fallout of 9/11 wasn’t just referenced in the crew’s lyrics — it’s reflected in their iconography. Their logo is a red-white-and-blue eagle toting two pistols. Juelz reflected his patriotism in a flag outfit that he wore in the “Dipset Anthem” video. He also wore a flag jacket in “Oh Boy,” a video that featured the whole crew wearing flag colors. When it comes to saluting America, it doesn’t get much simpler than wearing a flag.

Dipset's Diplomats, Volume 4 mixtape cover had a photo of a plane in the background. Photo Credit: Dipset

Dipset's Diplomats, Volume 4 mixtape cover had a photo of a plane in the background. Photo Credit: Dipset

Their most confounding 9/11 reference was their propensity for placing planes on the covers of their mixtapes. The group’s Diplomats, Volume 4 mixtape cover had a photo of a plane in the background, while mixtape covers for Dipset affiliates Purple City and S.A.S. depicted ominous planes in the sky. Perhaps the imagery was merely shock value or a subtle commentary on the violent pathologies shared by those ensnared in the “War On Terror” and the “War on Drugs.”

Today’s music will be a time capsule for the scourge of the Trump administration 20 years from now. Similarly, Dipset’s early 2000’s come up offers a glimpse of the era’s tumultuous cultural climate. While Nas, Diddy, Nelly and Ja Rule pled for answers on a somber “What’s Going On” redux and JAY-Z rhymed about sending “money and flowers” to 9/11 victims and Ghostface Killah declared "America, together we stand, divided we fall," Dipset canonized the biggest public enemies of the day — while wearing stars and stripes gear. In the early 2000s, the fear of terrorism was at an all-time high and patriotism was at a fever pitch.

It seemed only natural for a group named after government officials to cull inspiration from an assault on America.

__

This story was originally published in 2019.

Andre Gee is a New York-based freelance writer with work at Uproxx Music, Impose Magazine, and Cypher League. Feel free to follow his obvious Twitter musings that seemed brilliant at the moment @andrejgee.

Dipset's Diplomats, Volume 4 mixtape cover had a photo of a plane in the background. Photo Credit: Dipset

Dipset's Diplomats, Volume 4 mixtape cover had a photo of a plane in the background. Photo Credit: Dipset