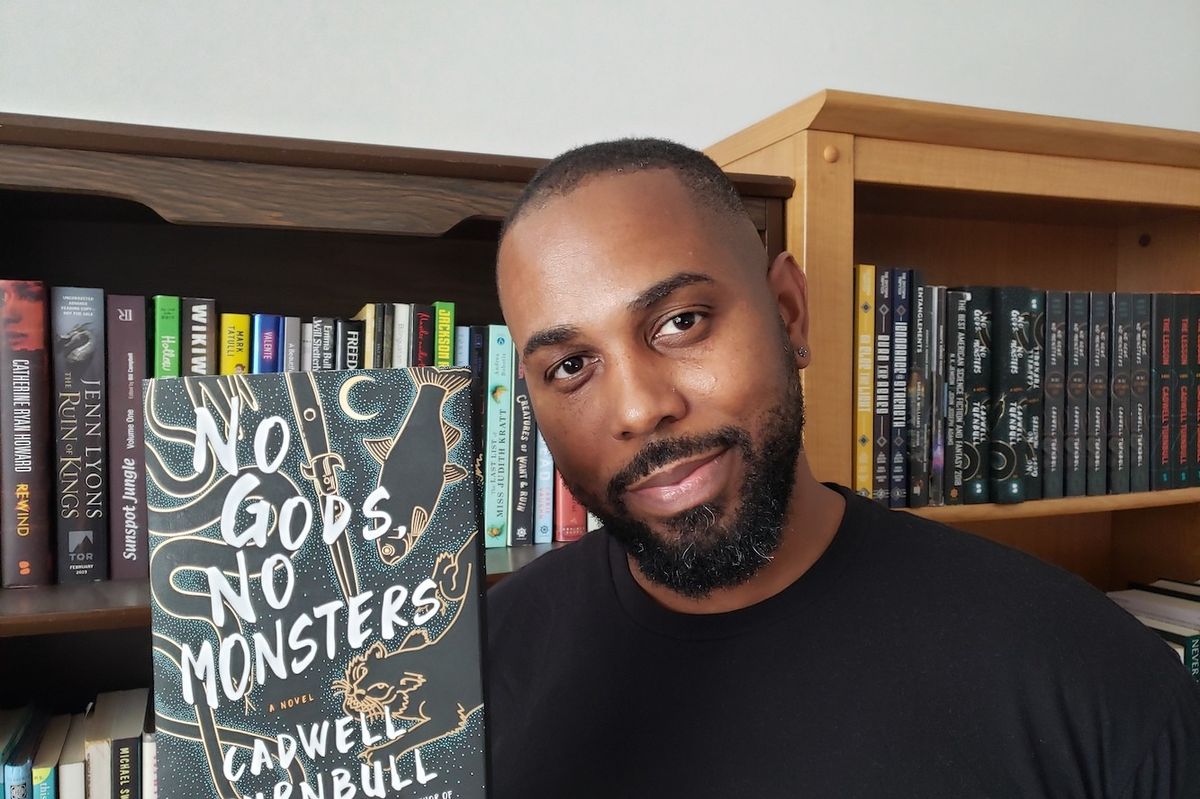

Cadwell Turnbull holding his book

Cadwell Turnbull, a veritable rising star in the Sci-Fi and Fantasy literary world, has published his second novel No Gods, No Monsters. Photo Credit: Anju Manandhar.

To continue reading

Create a free account or sign in to unlock more free articles.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Register

The content is free, but you must be subscribed to Okayplayer to continue reading.

THANK YOU FOR SUBSCRIBING

Join our newsletter family to stay tapped into the latest in Hip Hop culture!

Login

To continue reading login to your account.

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

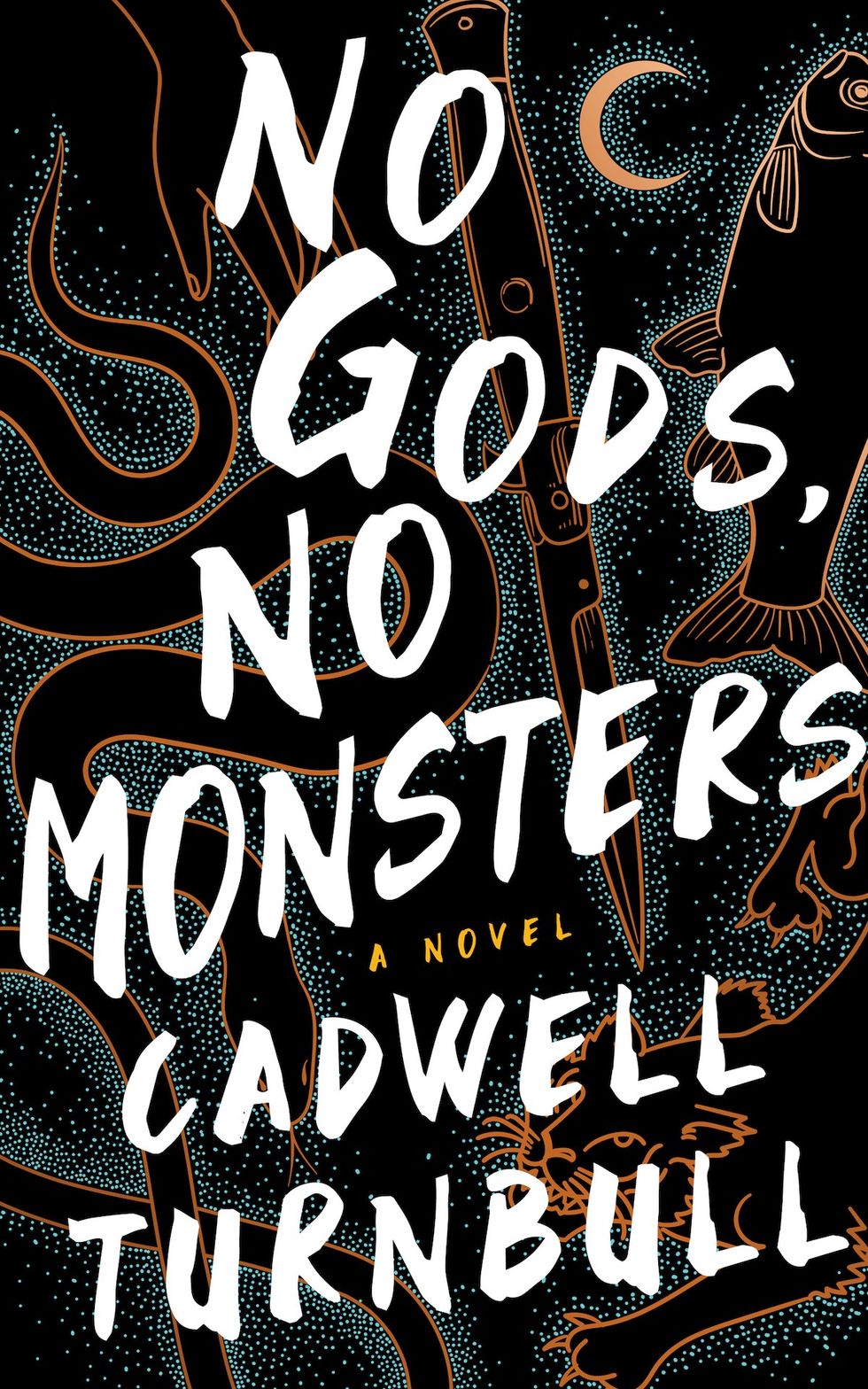

No human above, no human below. That’s the gist of the chant hundreds of people are shouting in the street near the end of No Gods, No Monsters, a new book by Cadwell Turnbull published last week (September 7th.) The title itself is an homage to an old anarchist slogan calling for the abolition of social hierarchies, and that is precisely what Turnbull questions in the many layers of the tale he weaves for readers. His basic premise: what if monsters were real and suddenly they all came out in the open? Underneath that main plot are storylines that wrestle with the societal ills that plague us: a leaked police shooting caught on shaky bodycam; acceptance of marginalized peoples; the risk in sharing our true selves; politics between the US and its territories; the power of the media to polarize; and determining right from wrong when everyone feels victimized. Turnbull explores all of this by deftly maneuvering through multiple narrators. Unraveling the story from the point of view of a werewolf or a dragon or a person whose brother was just killed by the cops.

Turnbull is a veritable rising star in the sci-fi and Fantasy literary world. He was born in Maryland but moved to his parents’ native St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands when he was a few months old. He was raised there by his granny and then came back to the continental US for college and now teaches Creative Writing at North Carolina State University. His debut novel, The Lesson, came out in 2019 and was well-received. It won the 2020 Neukom Institute Literary Award and was named "A Best Book of the Year" by numerous platforms. Two of his short stories, Jumpand Shock of Birth, were featured on the podcast LeVar Burton Reads.

Prior to No Gods, No Monsters being published, we spoke with Turnbull about his writing, the impact of growing up in the Virgin Islands, what it means to write fantasy during social unrest, giving marginalized characters voices in fiction, and more.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

What draws you to science fiction and fantasy?

Cadwell Turnbull: I always knew I wanted to be a writer, but I didn't know that you could write about certain subjects in this way. I feel like science fiction is really good at exploring big, societal questions from new or interesting angles and in such a way that it can slip under people's defenses and so the message can seep in. To be really, really honest, I just think science fiction and fantasy is fun. I just have more fun when I'm writing it and when I'm reading it and when I'm watching it.

Yes, there’s something about assessing an alien or a future society that lets people actually absorb things. They don’t get as defensive because they see the problem and don’t necessarily focus on their role in it or relation to it.

It's packaged differently, right? For example, in the book, there's an officer-involved shooting. If I went at that directly, some people would be able to receive it well, some people wouldn't, or I would have a harder time trying to get the larger message that I was trying to get with that to the reader. So using the genre tropes as metaphors — the werewolves are real in the story — but using them metaphorically in some ways and real in other ways allows people to latch onto the real stuff and then take some of the metaphorical stuff as well.

So then was the plot for No Gods, No Monsters new for you or had it been kicking around in your mind for a while?

I came up with a concept for the book after [my debut debut novel] The Lesson. I had just finished my revisions on [The Lesson] and wanted to pitch a book that could be part of a series. I already knew I wanted to be a little more experimental and philosophical with it, weird narratives and point of view.

The stuff happening under the surface of the book, that's been kicking around for a decade. Some of the characters I've drawn and written little bits or field stories about all through my 20s, but they never worked right in any of those other settings. When I tried introducing them to the main plot of this story, it just made a lot of sense on a lot of different levels.

The subject matter of No Gods, No Monsters aligns closely with current events. Was that just coincidence or what was the timeframe?

During my last year of my MFA, around 2015 and 2016, there was a lot of video footage of people being shot. It was like a season. Mostly Black men. People were making comments on social media. Some of them were bigoted comments. I wanted to try to talk to people and try to reason with people to help them understand what was going on. I thought, “maybe they haven't had this explained.” I wrote a lot of Facebook posts and they would write back. It got heavier and heavier. I became pretty depressed.

I don't do that anymore. But when putting this pitch together for this book, I remembered that season of Black men being killed. I thought: “What if during all that we were to discover werewolves are real and they've been hidden successfully for a really long time.” The idea of it being discovered via bodycam footage came to me pretty early. As I was working that idea out, George Floyd was murdered. Then all the protests happened while I was working on the edits. I had a lot of passion and a lot of emotions and I was very depressed and I was very weighed down. Then there was also the pandemic.

I just felt very powerless. I remember wanting to be out and angry in the streets, but also feeling like we risk ourselves every day and then we have to risk ourselves even more so that society will listen to us. We're out there risking potentially getting sick and passing away. I had just lost my friend to COVID[-19]. The book became a way for me to do something. I'm still hard on myself about that time —wishing I was doing more. But it was something that I could do and it helped me process some of what was going on.

If you are actively preserving yourself, I think that's doing something. To take on the task of making sure you can function in a way that is familiar to you… I mean, it was very difficult. It still is. I’m incredibly sorry to hear about your friend and the fact that the virus is something we’re still trying to understand and people are debating it—

I do want to say something about the debating of it. When I was working on the book — this is another kind of weird synchronicity — I was thinking through how people might respond to the fact that monsters were coming out of the shadows. At first, I had it so everyone accepted it. But as I kept working, it became pretty clear to me that there would be a split. That would cause its own tensions within society, and it would be a kind of unspoken agreement that there's now two versions of reality that are true. Then the pandemic showed us that that's exactly how we are. Something can be very, very real, and half of us will look away or debate it, and then half of us will look at it and be like, "Yeah, this is real." Then we'll be pretty angry or frustrated with each other for coming to these different conclusions.

Had it always been set in 2023?

It was originally in the modern day, but the pandemic changed that. It’s funny, when the pandemic started, there were all of these conversations that were happening, particularly with speculative fiction writers, about how strange it is to be living through a genre of books that you've read because the pandemic genre is a subgenre of science fiction.

We were also talking about how more traditional literary writers who would write about COVID now would be writing about a subgenre of science fiction, but it wouldn't be science fiction anymore. I find that really fascinating. But at the same time, I didn’t want to have a pandemic happening along with werewolves and the other subplots. So I pushed it just a bit into the future.

Both your novels have plot lines set in the Virgin Islands. In fact, the islands definitely play a character. What is your intention behind the framing of the location?

I grew up there from a few months old to when I left for college. There's no other home for me. When I step off the plane, there's a different feeling, like a spirit that inhabits me that is unique to that place that I don't feel anywhere else.

Yet during my MFA, I was telling these stories set in all kinds of other places, not there. My advisor was like, "You should write about home." I don't know if for him it was a throwaway suggestion, but for me, it was earth-shaking. Then I started doing it and was able to tap into real human emotion and a lot of things that I would struggle with in other stories, because I was keeping so much of myself from it. I was not integrating whole parts of me to the work.

We have so many stories about American or white people or people from dominant cultures taking their perspective and projecting it onto someplace they would call exotic. We have the American perspective about Brazil or Kenya or wherever. It seemed really important to me to flip that. What if you could have the Virgin Islands perspective about Boston or the Virgin Islands perspective about North Carolina? Why isn't that a possible thing? It's one of the reasons I play with the narrator or narrative perspective in the book.

I felt like we kind of take for granted that the European or the Western dominant third person narrator omniscient narrator is the norm. It's harder for people to accept a third person narrator that is more vernacular. Even if it's a bit difficult sometimes, I think that's important. Fiction shouldn't always be comfortable, for a writer and a reader.

No Gods, No Monsters has a clever play on paranoia. Who are the good guys, who are the bad and can you be sure? There’s a tug-of-war between victimhood and righteousness.

There's two secret societies that are a big part of the book. They're in constant conflict or truces with each other, depending on the era. In this era, they're kind of like in an unsteady truce that they know is going to fail, that eventually this is going to turn into an all out conflict. One of them seems pretty clearly evil and one of them seems ambiguously good.

Then there's the characters that are hitting up against these secret societies and they're seeing weird things happening around them. They're so terrified that it traumatizes them into inaction or into solitude. Things that they would normally share with their lovers, they don't want to say out loud because they are afraid themselves of what it might mean. They're trying to protect each other with silence. I wanted to explore the fact that all characters, even the ones who seem like they could be completely bad, have motivations that they consider to be righteous.

One of my favorite things about the book is that the majority of characters are what we would consider minorities: brown people, Black people, trans people, homosexual or asexual people. Typically these characteristics mark the “us” and “them” in narratives. But, you create a new “us” and “them” that supersedes these other delineations. I’d like to hear from you what your intention was in that.

I'm a Black man. I'm Afro-Caribbean. I grew up in the Virgin Islands, but I'm a writer. I think a lot about philosophy. I have big questions about creation. I love movie scores. I'm a big fan of films.There's all of these aspects of me that are parts of my identity that I think are really important parts of me that are not just my Blackness or the fact that I'm Afro-Caribbean.

There's a way that dominant culture and society make marginalized people one aspect of themselves to care about them. It was important to me that if I don't like that when it comes to me, I wasn't going to do that to any of the characters in the book. I wanted it to be just a part of that person and have that exist and have them be loved by the people around them. They hit up against some things in society, but they spend a great deal of time not thinking about themselves in that kind of label, because I spend a great deal of time not contextualizing myself in a way that others might hate me, if that makes any sense.

As whole people, even people that are marginalized, it takes them time to see the marginalizations of others. It takes people time to see their own privilege. It isn’t guaranteed that the trans characters or queer characters will automatically accept people who come out as werewolves, you know? We all have to process the world around us.

If you could be one of the types of monsters in the book, who's your fighter?

Today, I kind of like Damsel. She has magic tattoos. She's kind of snarky. I think I would want to have magic tattoos today. Sometimes I want to be Dragon.

The book doesn’t end with a concrete resolution and quite a bit of carnage. Can we look forward to a sequel for the survivors?

Dragon is going on a three-book arc. Through the secret societies and then on a journey towards himself. And one of the most mysterious characters, Asha, leader of one of the secret societies… she will eventually be revealed.

__

Nereya Otieno is a writer, thinker and ramen-eater currently based in Los Angeles.